A research team from MIT and Stanford University has developed a new technique designed to push the immune system to go after tumor cells. The strategy is aimed at helping cancer immunotherapy succeed in far more patients than it does today.

At the center of the work is a way to undo a built in “brake” that tumors can trigger to keep immune cells from attacking. That brake is tied to sugars called glycans, which sit on the surface of cancer cells.

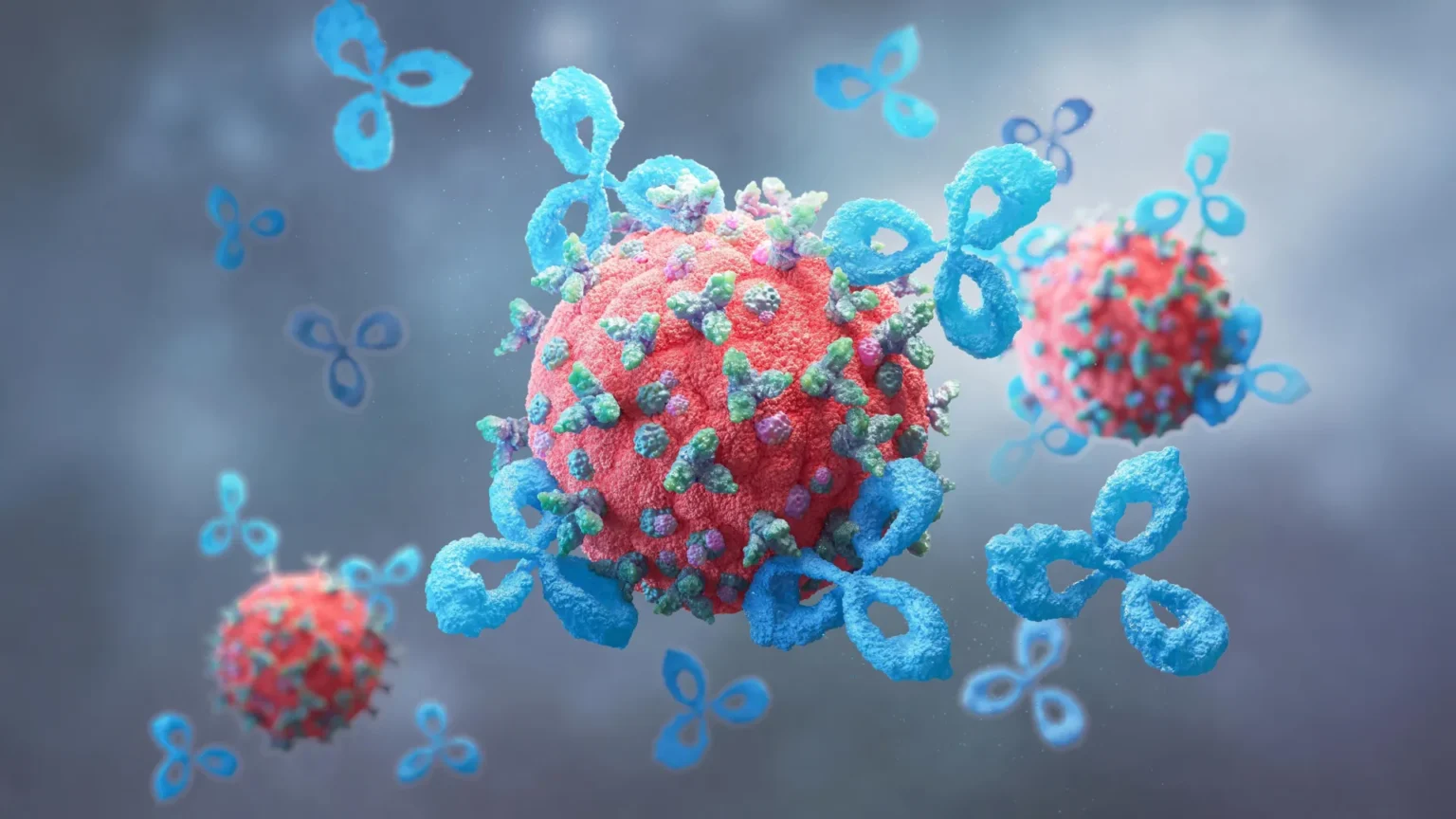

The scientists found that blocking these glycans with proteins known as lectins can greatly strengthen immune activity against cancer cells. To do this in a targeted way, they built multifunctional molecules called AbLecs that pair a lectin with an antibody that homes in on tumors.

“We created a new kind of protein therapeutic that can block glycan-based immune checkpoints and boost anti-cancer immune responses,” says Jessica Stark, the Underwood-Prescott Career Development Professor in the departments of Biological Engineering and Chemical Engineering. “Because glycans are known to restrain the immune response to cancer in multiple tumor types, we suspect our molecules could offer new and potentially more effective treatment options for many cancer patients.”

Stark, who is also a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, led the study as the paper’s lead author. Carolyn Bertozzi, a Stanford professor of chemistry and director of the Sarafan ChEM Institute, served as the senior author. The findings were published in Nature Biotechnology.

How Cancer Uses Immune Brakes

One of the biggest goals in cancer treatment is teaching the immune system to spot tumor cells and eliminate them. A major group of immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors works by interrupting the interaction between two proteins, PD-1 and PD-L1. By blocking that connection, these medicines remove a brake that tumors use to keep immune cells such as T cells from killing cancer cells.

Checkpoint inhibitors that target the PD-1 PD-L1 pathway are already approved for several cancers. For some people, they can produce long lasting remission. For many others, however, they provide little benefit or none at all.

Because of that gap, researchers are searching for other ways tumors suppress the immune system. One promising target involves interactions between tumor glycans and receptors on immune cells.

Siglecs, Sialic Acid, and a Sugar Based Checkpoint

Glycans appear on nearly all living cells, but cancer cells often carry versions not found on healthy cells. Many of these tumor specific glycans include a sugar building block called sialic acid. When sialic acids attach to lectin receptors on immune cells, they can switch on an immune dampening pathway. The lectins that recognize sialic acid are called Siglecs.

“When Siglecs on immune cells bind to sialic acids on cancer cells, it puts the brakes on the immune response. It prevents that immune cell from becoming activated to attack and destroy the cancer cell, just like what happens when PD-1 binds to PD-L1,” Stark says.

So far, no approved medicines directly target the Siglec sialic acid interaction, even though many approaches have been explored. One idea has been to create lectins that bind to sialic acids and block their contact with immune cells. But this has struggled because lectins typically do not bind strongly enough to build up in large numbers on the surface of cancer cells.

AbLecs Combine Antibodies and Lectins

To solve that problem, Stark and her team used antibodies as delivery vehicles to bring more lectins to tumors. The antibody portion targets cancer cells, and once it arrives, the attached lectin can bind sialic acid. That blocks sialic acid from engaging Siglec receptors on immune cells, which lifts the immune brake and lets immune cells including macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells attack the tumor.

“This lectin binding domain typically has relatively low affinity, so you can’t use it by itself as a therapeutic. But, when the lectin domain is linked to a high-affinity antibody, you can get it to the cancer cell surface where it can bind and block sialic acids,” Stark says.

A Plug and Play Design Tested in Cells and Mice

For this study, the researchers built an AbLec using trastuzumab, an antibody that binds to HER2 and is approved for treating breast, stomach, and colorectal cancers. To create the AbLec, they replaced one arm of the antibody with a lectin, choosing either Siglec-7 or Siglec-9.

In lab experiments with cultured cells, this AbLec changed how immune cells behaved, pushing them to attack and kill cancer cells.

The team also tested the AbLecs in mice engineered to express human Siglec receptors and human antibody receptors. After the mice were given cancer cells that formed lung metastases, treatment with the AbLec led to fewer lung metastases than treatment with trastuzumab alone.

The researchers also demonstrated that the approach is flexible. They could swap in different tumor targeting antibodies such as rituximab, which targets CD20, or cetuximab, which targets EGFR. They could also exchange the lectin portion to target other immunosuppressive glycans, or use antibodies that target checkpoint proteins such as PD-1.

“AbLecs are really plug-and-play. They’re modular,” Stark says. “You can imagine swapping out different decoy receptor domains to target different members of the lectin receptor family, and you can also swap out the antibody arm. This is important because different cancer types express different antigens, which you can address by changing the antibody target.”

Next Steps and Funding

Stark, Bertozzi, and colleagues have launched a company called Valora Therapeutics to develop lead AbLec candidates. They aim to start clinical trials in the next two to three years.

Funding for the work came in part from a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award at the Scientific Interface, a Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer Steven A. Rosenberg Scholar Award, a V Foundation V Scholar Grant, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, a Merck Discovery Biologics SEEDS grant, an American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship, and a Sarafan ChEM-H Postdocs at the Interface seed grant.