Northern Japan, especially the island of Hokkaido, is home to some of the snowiest cities in the world. Sapporo, the island’s largest city and host of an annual snow festival, typically sees more than 140 days of snowfall, with nearly 6 meters (20 feet) accumulating on average each year. The ski resorts surrounding the city delight in the relatively dry, powdery “sea-effect” snow that often falls when frigid air from Siberia flows across the relatively warm waters of the Sea of Japan.

However, despite the region’s familiarity with heavy snowfall, winter 2026 got off to a disruptive start. A series of intense storms in January and February repeatedly paralyzed transportation systems, closing airports, snarling roadways, and suspending trains. Following storms that dropped more than 2 meters (7 feet) of snow in Aomori, a city on the island of Honshu just south of Hokkaido (out of frame), authorities deployed troops to help clear roofs, according to news reports. The snow has caused dozens of deaths and hundreds of injuries, according to Japan’s Fire and Disaster Management Agency.

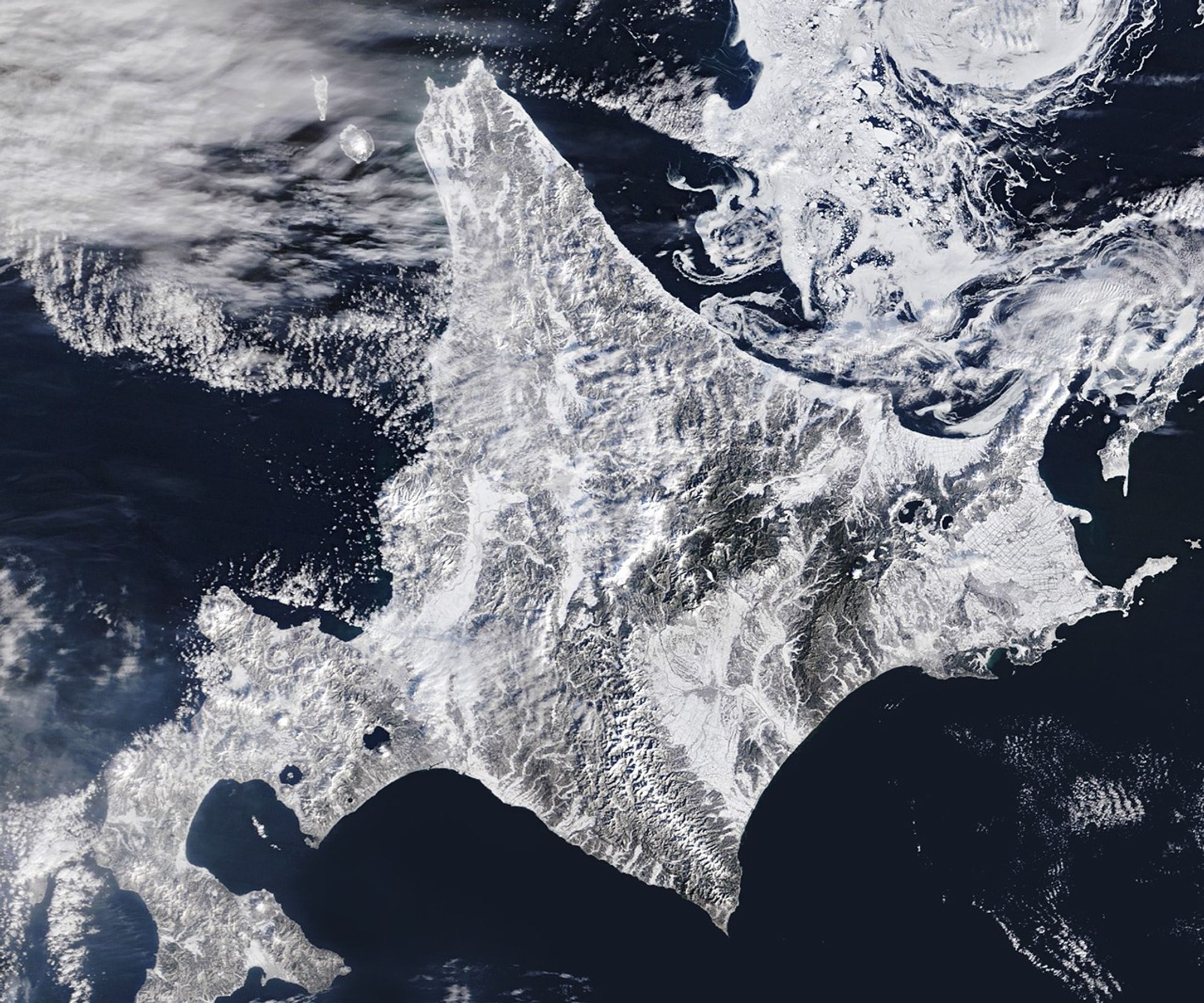

On February 5, 2026, the MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) on NASA’s Terra satellite acquired this image of snow-covered landscapes across Hokkaido. With more than 31 active volcanoes, the island features several large caldera lakes, including at least five that are visible in the image. (Calderas are large depressions formed by volcanic eruptions.) In the east, forested windbreaks around Nakashibetsu form a checkerboard pattern, while to the north, swirls of drifting sea ice adorn the Sea of Okhotsk.

The Sea of Okhotsk is the southernmost sea that routinely hosts large amounts of sea ice. Although this winter brought unusually cold weather, long-term observations indicate that the amount of ice observed there each year has declined significantly in recent decades. One 2026 analysis noted a 3.4 percent per decade decline in the maximum extent of its winter sea ice since the 1970s. These changes could have implications for the region’s marine ecosystems, which are known for being highly productive and producing massive phytoplankton blooms each spring after the ice melts.

Disruptive snowstorms are also striking elsewhere in Japan. In February, a storm blanketed western Japan in snow, leading to more travel disruptions and the early closure of some polling stations during national elections.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Michala Garrison, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Adam Voiland.

- AccuWeather (2026, February 3) Snow piles nearly 7 feet high as deadly storms bury northern Japan. Accessed February 9, 2026.

- Associated Press (2026, February 4) Heavy snow in northern Japan blocks roads and causes dozens of deaths. Accessed February 9, 2026.

- The Japan Times (2026, February 4) Japan warns of avalanches as snow deaths rise to 35. Accessed February 9, 2026.

- The Mainichi (2026, January 26) Heavy snow strands 7,000 travelers at Hokkaido’s ‘landlocked’ New Chitose Airport. Accessed February 9, 2026.

- Narita, D. & Iwasaki, S. (2026) Past and Future Changes in Sea Ice in the Sea of Okhotsk: Analysis Using the Future Ocean Regional Projection Dataset. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 52.

- The New York Times (2026, February 8) Heavy Snow Disrupts Japan Election, Forcing Polling Stations to Close Early. Accessed February 9, 2026.

- NHK World Japan (2026, February 8) Snow piles up rapidly in western Japan. Accessed February 9, 2026.

- Skiing Hokkaido (2013) Meteorologist Mr. Mori explains ~ Why “good snow” falls in Hokkaido. Accessed February 9, 2026.

- Steenburgh, W.J. & Nakai, S. (2020) Perspectives on Sea- and Lake-Effect Precipitation from Japan’s “Gosetsu Chitai.” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 101(1), E58-E72.

- World Meteorological Organization (2026, February 3) Extreme heat, cold, precipitation and fires mark the start of 2026. Accessed February 9, 2026.