The grand prize would be a room-temperature superconductor, a material that could transform computing and electricity but that has eluded scientists for decades.

Periodic Labs, like Lila Sciences, has ambitions beyond designing and making new materials. It wants to “create an AI scientist”—specifically, one adept at the physical sciences. “LLMs have gotten quite good at distilling chemistry information, physics information,” says Cubuk, “and now we’re trying to make it more advanced by teaching it how to do science—for example, doing simulations, doing experiments, doing theoretical modeling.”

The approach, like that of Lila Sciences, is based on the expectation that a better understanding of the science behind materials and their synthesis will lead to clues that could help researchers find a broad range of new ones. One target for Periodic Labs is materials whose properties are defined by quantum effects, such as new types of magnets. The grand prize would be a room-temperature superconductor, a material that could transform computing and electricity but that has eluded scientists for decades.

Superconductors are materials in which electricity flows without any resistance and, thus, without producing heat. So far, the best of these materials become superconducting only at relatively low temperatures and require significant cooling. If they can be made to work at or close to room temperature, they could lead to far more efficient power grids, new types of quantum computers, and even more practical high-speed magnetic-levitation trains.

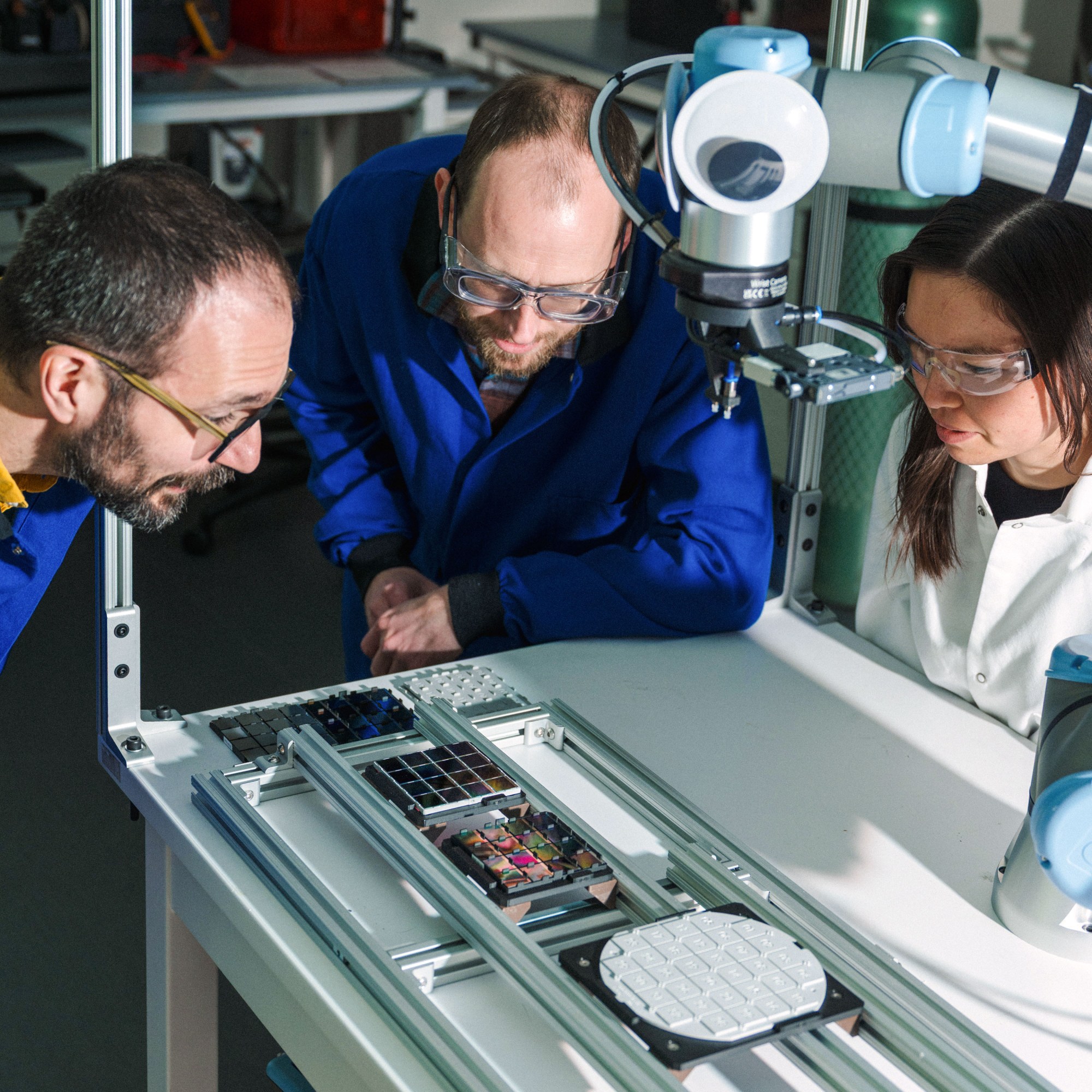

CODY O’LOUGHLIN

The failure to find a room-temperature superconductor is one of the great disappointments in materials science over the last few decades. I was there when President Reagan spoke about the technology in 1987, during the peak hype over newly made ceramics that became superconducting at the relatively balmy temperature of 93 Kelvin (that’s −292 °F), enthusing that they “bring us to the threshold of a new age.” There was a sense of optimism among the scientists and businesspeople in that packed ballroom at the Washington Hilton as Reagan anticipated “a host of benefits, not least among them a reduced dependence on foreign oil, a cleaner environment, and a stronger national economy.” In retrospect, it might have been one of the last times that we pinned our economic and technical aspirations on a breakthrough in materials.

The promised new age never came. Scientists still have not found a material that becomes superconducting at room temperatures, or anywhere close, under normal conditions. The best existing superconductors are brittle and tend to make lousy wires.

One of the reasons that finding higher-temperature superconductors has been so difficult is that no theory explains the effect at relatively high temperatures—or can predict it simply from the placement of atoms in the structure. It will ultimately fall to lab scientists to synthesize any interesting candidates, test them, and search the resulting data for clues to understanding the still puzzling phenomenon. Doing so, says Cubuk, is one of the top priorities of Periodic Labs.

AI in charge

It can take a researcher a year or more to make a crystal structure for the first time. Then there are typically years of further work to test its properties and figure out how to make the larger quantities needed for a commercial product.