Peter couldn’t understand how his healthy lifestyle could have led to what happened but the GP claims that is exactly what saved his life.

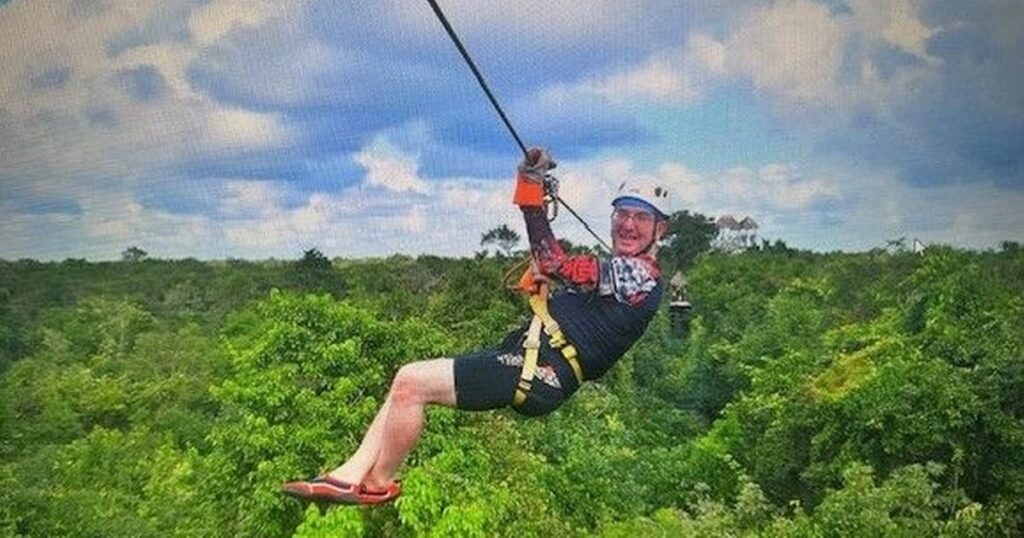

Just days before his heart stopped beating, Peter Heathcote was dangling from a bungee cord in Mexico. Soon after he was sprinting up a Welsh mountain, pausing only to let his younger friend catch up. Life was always full-throttle—until, suddenly, it wasn’t.

At the age of 55, Peter wasn’t someone you’d ever expect to suffer a cardiac arrest. He wasn’t just fit for his age—he was active, energetic and constantly on the move. From horse-riding across the Andes in Peru last spring to running a nine-acre smallholding in Risca with his wife Katherine and children, he lived life at pace.

“We’ve always been busy people,” Peter, from Caerphilly, admits. “Even after we retired in 2016, it wasn’t really retirement. We’ve got horses, sheep, chickens, dogs—and we use the land to run community events. In September we hosted an event for vulnerable people including survivors of abuse and cancer, introducing them to Icelandic horses. There is always something going on!”

Peter’s lifestyle was as healthy as it was active. He had regular blood tests and each time the results were solid. His BMI was around 25.5, he didn’t smoke, and though he enjoyed a glass of wine now and then, it was nothing excessive. His doctor had even given him a clean bill of health—a routine score known as a Q-score showed that, if anything, he was at low risk of any cardiac events.

“I’ve had routine blood tests and all of them were good. No issues were flagged at all,” he recalls. “The doctors would do a Q-score, and even my GP said that if I’d done that a month before my cardiac arrest, I would have been right at the bottom of the risk scale.”

That’s what made what happened next so unexpected. Stay informed on the latest health news by signing up to our newsletter here

On the evening of January 22 this year Peter felt a little more tired than usual, but he put it down to jetlag after flying home from Mexico. “I went to bed early, I didn’t think much of it. There were no other symptoms to suggest that something else was going on.”

The next morning, things took a rapid change for the worst. “I woke up with a significant pain in my chest and thought to myself maybe I had some indigestion or heartburn. I couldn’t quite decide what was happening really,” Peter shared.

“I got ready for a meeting that I was having that day and within a very short space of time, started to feel nauseous and there was pain in my arms.”

Even as his symptoms intensified, he hesitated to call for help. “When something like this happens, you do think to yourself ‘this is something minor’ and try to rationalise it,” Peter says.

“The other thing, that all of us is painfully aware of, is the NHS is so stretched out—so busy—that we don’t want to waste anyone else’s time.

“As things progressed rapidly, when you realise that you’re not in a good way and you do need that help, there is still a part of you that doesn’t want to make a nuisance of yourself. I think a lot of people are like that.”

However, the intensifying pain became harder for Peter to ignore. “The pain in my chest became a crushing pain, which then moved to my jaw, so I was unable to speak.”

His wife called 999 while their two 18 and 21-year-old children stayed close by. At one point, the operator informed the family that it could take up to two hours for an ambulance to arrive. “I couldn’t see anything but I could hear bits,” Peter commented. “When you hear that it could be two hours before you could get any help it’s hard not to think ‘I’m not going to make it.'”

But thanks to a quick redirect from the control team, a rapid response vehicle and ambulance made it to his home. A team of four paramedics began treatment immediately, administrating GTN sprays, blood thinners and IV medication right there in the living room, while monitoring Peter’s plummeting vital signs. His breathing had dropped to a terrifying three breaths per minute.

With blue lights flashing, Peter was rushed to the University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff arriving around 10.30am. There was no waiting. He was wheeled straight into theatre, where doctors discovered a severe blockage in his left anterior descending artery, known ominously in cardiology circles as the “widow maker.”

“They put a single stent into my heart and I felt the relief almost instantly,” Peter says. “The crushing pain lifted. I was incredibly lucky.”

By mid-afternoon, he was sitting in intensive care eating dinner and even took a phone call about a charity event he was organising for March.

“They asked if it was a good time to talk,” he laughed. “I said, ‘Well, I’ve just come out of theatre, but I’m not going anywhere—I’m wired to the wall.'”

The days following his cardiac arrest were a blur of emotions, intense relief and a new sense of vulnerability. Yet in the quiet of his hospital room, the weight of the situation began to sink in; Peter couldn’t help but question everything.

“While I was in intensive care, I started thinking ‘how is this possible’? I’ve really tried to do the right things. I’ve looked after myself, kept fit, been a non-smoker—this is strange.”

But there was one factor no Q-score or blood panel had flagged clearly: family history. “In my case, my father had a heart attack,” Peter said. “He was a smoker all his life, and I thought to myself, that must have been the big contributing factor. It didn’t really make me do anything.”

That’s changed. Since his cardiac arrest, Peter’s siblings and his children have all undergone lipoprotein testing; a genetic marker that’s not included in routine checks. Following this, his middle son was referred to a lipid clinic for elevated LP(a), while Peter’s sister has been started on statins, a class of medications primarily used to lower cholesterol levels in the blood to lower the risk of heart disease and stroke.

“In a way, my heart attack has helped save two of my family members from a similar fate. That’s a positive I can take from this whole ordeal,” he says.

In the midst of his own confusion, one of the consultants offered an explanation that struck Peter deeply. “They said there were a couple of ways to look at this,” he says. “One way was that if I hadn’t looked after myself, hadn’t kept my health in check, this would have happened 10 or 15 ago.

“The other way to look at it is that if I hadn’t taken care of myself, I would’ve been dead.”

That realisation helped shift Peter’s mindset. Instead of dwelling on the negative, he made a conscious decision to focus on the positives. He now looks back on his experience with a sense of gratitude that has helped him keep his sanity.

“The only way I can process what I’ve been through,” Peter says, “is to think of the positives. I was so lucky this didn’t happen on a plane, or while I was bungee jumping in Mexico. I wasn’t alone. You start thinking to yourself ‘I’m actually a really lucky guy.'”

One positive Peter has come to learn in the months following his heart attack is the outstanding service that the cardiac rehabilitation team provide. “The cardiac rehab team at St Woolos are nothing short of incredible. So understanding. So bubbly and positive, even though they’re completely rammed.”

Peter went onto explain how the weeks after his heart attack were a mental minefield—moments of doubt, flickers of fear, and constant questions about whether it might happen again. However, St Woolos helped him pull through.

“As soon as you come out of hospital, they book you in and they start going through absolutely everything,” he says. “Twice a week you’re going in and doing this workout under their supervision, to get you back to normal—or as normal as possible, although you do have to take a lot of medication from that point on.”

It wasn’t just about treadmills and blood pressure checks—it was emotional too. “They let you talk through the flurry of emotions, the shock, and the fact you’ve suddenly realised your own mortality.”

Peter was offered counselling as part of the programme, which helped make sense of the experience. “You can imagine after something like this, every time you get a weird feeling in your chest, or a bit of acid reflux, your brain goes straight to: is this happening again? You’re constantly on edge. You become hyper-aware of everything your heart does.”

And then there’s the physical reality of the stent now inside him. “I’ve now got a foreign body in my heart. I can kind of feel it—it’s a weird thing to explain. For the first month, it felt like something was just… there. It’s really strange.”

What made all the difference, he says, was the accessibility and compassion of the rehab team. “You can ring them or email them and they get back to you so quickly. If you feel lightheaded or have symptoms, they’ll talk you through it. They never make you feel silly or like a burden—they just get it.”

That personal connection inspired Peter to give something back. In June, he’s hosting a fundraiser for the cardiac rehab team at the Junction 28 restaurant in Newport on June 23 with the aim of raising enough money to buy them a 12-lead ECG machine.

Right now, patients have to be referred back to their GP or the Gwent for even a basic ECG. The process can take weeks—time that, as Peter knows, some people just don’t have. “It would be huge for the team to have their own machine. It just takes a minute, and it could literally save lives,” he says. “That simple machine can make a massive difference to a lot of people’s lives.”

The event promises to be a night to remember, featuring a three-course meal, a raffle with fantastic prizes including a mystery celebrity-donated prize and an experience to swim with alligators in Bristol.

There will also be opportunities for people to sponsor tables, with packages for £200 for five guests and £400 for ten. For those unable to attend, there’s the option to sponsor a place or a table for NHS cardiac staff. To reserve spaces for the fundraising event, please contact Peter Heathcote at contact@peterheathcote.co.uk.

The evening will be graced by Rhianon Passmore MS as well as Cerri Kostin, the very cardiac nurse who guided Peter through his recovery. Cerri will speak from her heart, sharing her first-hand experience with patients like Peter. “She is charismatic and funny,” Peter says. “Most importantly, she sees it all first-hand. That’s what people need to hear.”

Peter hopes that through the support of this event and GoFundMe page not only will the team at St Woolos Hospital get the equipment they need but others will be inspired to appreciate the importance of living fully. “The weirdest thing is that I’ve always said to people ‘No one promises you tomorrow,'” Peter reflects. “And now, more than ever, I truly understand what that means.”

Looking ahead, Peter hopes that his fundraiser for the cardiac rehab team will not only provide life-saving equipment, like the ECG machine, but also raise awareness about heart health. “If this event can help even one person avoid what I went through, then it will all have been worth it,” Peter says. “I just want to make sure that no one else has to face the same uncertainty and fear that I did.”