The latest labour market figures are a study in ambiguity, giving no clear signs to the Bank of England on when interest rates should be cut.

There’s clear signs that the labour market is loosening.

Unemployment has increased for four consecutive months, rising from 3.8 per cent at the end of 2023 to 4.4 per cent at the moment.

That means unemployment is at its highest level since September 2021 and an extra 190,000 people are out of a job.

It also means the unemployment rate is just a touch below the Bank of England’s estimate of the natural rate of unemployment, the level of unemployment at which inflation does not increase.

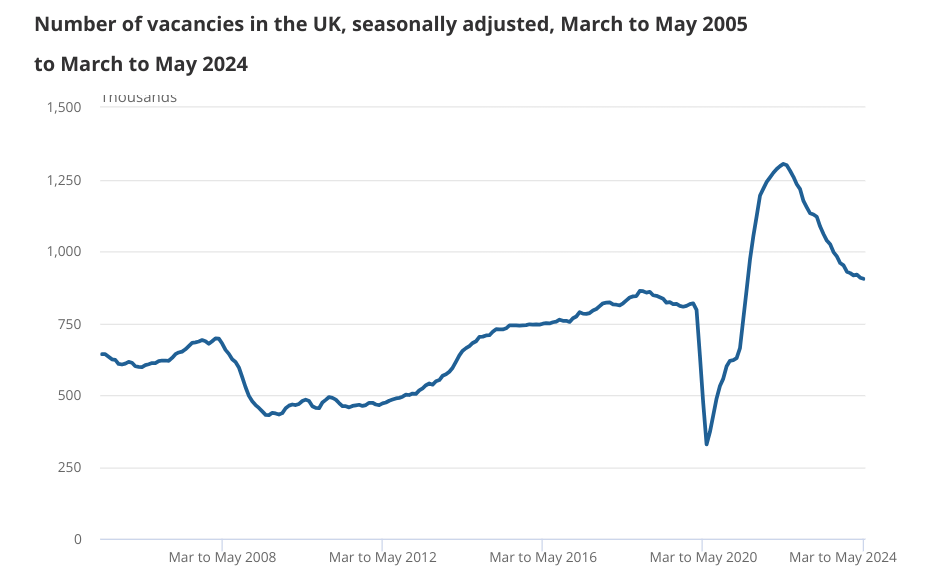

Other measures also show that the labour market is cooling. Vacancies have fallen for 23 out of the past 24 months.

The fall in vacancies and the rise in unemployment means that the vacancy-to-unemployment ratio, a measure of labour market tightness, is now below the pre-Covid level.

In other words, its clear that sluggish economic activity – caused in part by higher interest rates – is having a meaningful impact on the labour market.

“The labour market is gradually easing,” Rob Wood, chief UK economist Pantheon Macroeconomics said.

And yet this is not translating into lower wage growth. Regular pay growth remained at 6.0 per cent between February and April. Including bonuses, pay was stuck at 5.9 per cent, unchanged after last month’s figures were revised up.

This is, by now, a familiar pattern: wage growth remains stubbornly high even though there are signs that the labour market is weakening.

Policymakers at the Bank of England will want to see more compelling movements on wage growth before starting to bring interest rates down.

However, there are some more encouraging signs on wage growth (at least as far as the Bank of England is concerned) if you look underneath the hood. Regular pay growth in the private sector, which the Bank cares more about than the overall figure, cooled to 5.8 per cent from 5.9 per cent.

The overall figures were also kept artificially high by April’s near 10 per cent increase in the minimum wage.

About half of the monthly increase in pay was likely a result of the minimum wage increase. Neil Carberry, chief executive of the Recruitment and Employment Confederation (REC), described the pay data as “noisy”.

Once the impact of the minimum wage hike has filtered through, then wages should start to trend downwards more reliably. This means an August rate cut is certainly still on the cards, even if June is firmly off the table.

As ever it depends on how the data comes in. Pantheon’s Wood pointed out that it would be “unusual” to cut rates while pay growth was so strong. An August cut is not a “slam dunk,” he said.

Ruth Gregory, deputy chief UK economist was more hopeful. “The stickiness of wage growth may not stop the Bank from cutting interest rates for the first time in August…as long as other indicators such as pay settlements data and next week’s CPI inflation release show decent progress”.