With over 25 million players in more than 90 countries, padel has been taking the world by storm, and has frequently been reported as the fastest-growing sport across the globe. Spain has six million players, and over 20,000 courts. Italy is the fastest new adopter of the sport, making up 18.5% of all global Google searches for ‘Padel’ and over 5,000 courts. Overall in Europe in 2023, 15,000 new padel courts were constructed and by 2026, the number of padel courts is expected to more than double (+112.5%) to 85,000.

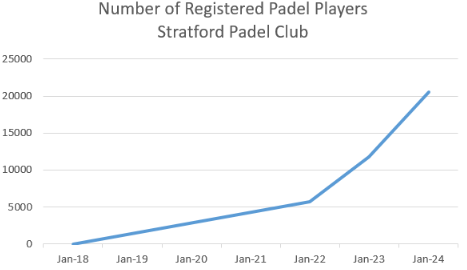

Since 2018, the number of UK padel players has increased by almost 60x with over 175,000 active padel players registered to date, according to the Lawn Tennis Association (LTA). In the last 12-months alone, the number of registered padel players at Stratford Padel Club saw a 100% increase, and are only able to accommodate bookings for corporates from the end of May onwards, even with nine courts operating seven-days a week, 15.5-hours per day. Companies are understanding the power of padel as a tool for team building, with hundreds of businesses organising repeat corporate events, due to the sport’s accessibility. The pop-up padel court installed by the Central London Alliance (CLA) in Tower Hill last year acted as an incentive to bring workers and visitors into the capital. It was fully booked on countless occasions including on all weekends and Bank Holidays with over 80% occupancy, 13-hours a day, seven-days a week.

At the end of 2022, 150 courts existed in British facilities and according to the LTA, a year on, and only 130 more courts have been built in the UK. A fact that the LTA reported as ‘a significant increase’, but compared to the thousands being built per year in other European countries, this is nothing to be celebrated. On Monday, The Telegraph reported that those erected courts were almost entirely driven by private investors, with the LTA only establishing 3 courts in the UK since the start of padel in 2014. The UK is lagging behind in supporting this fast growth sector, and there is much still to do.

The demand is clearly outstripping supply, so why aren’t we seeing more padel courts across the UK?

There are three major obstacles repressing the growth trajectory in the UK.

Space – particularly indoors

Whilst padel is played across many outdoor courts throughout Europe, although no major professional tournament is held outdoors, the infamous unpredictable Great British weather does not lend itself well to the outdoor provisions of the sport and indoor courts are better suited.

On permanent courts, the ground playing surface is coated with sand, when humid or after rain, the bounce of the ball is affected. Rain and humidity can also impact the glass panels, which are critical to play, forcing the ball to skid off the glass and the game becomes unplayable.

The ‘lob’ (the most used hit in a professional game – 85.4%) and the success of this shot if played outdoors is also dependent on weather elements. Tennis is far less affected as the groundstrokes are more dominant.

All these factors impede the sport if played in adverse weather conditions and in turn have a negative impact on the sports’ participation levels, court occupancy and thereby revenue together with maintenance costs, and longevity of the courts. Stratford Padel Club reported that the occupancy rate of their outdoor court was approximately 50% compared to the rest of their indoor facilities (an offering during lockdowns for 12-months).

Of course, if you are looking to activate a space and place a pop-up short term court, just like CLA did over the summer months, outdoor pop-up courts are well placed, but for long-term sustainable solutions these factors need to be overcome.

Planning Permissions

Once the space is found, planning permissions are another hurdle. Planning remains a long and complex process, with the average duration from start to approval of approximately eight to ten months for a padel club with a minimum of four courts.

Many councils have been known to reject the sport’s installation. The benefits of inserting a sporting facility for public use and improving health and wellbeing should go without saying. Padel can be played by people of all ages and skill levels, with 30% of padel players being women compared to just 15% in tennis. Planners should embrace the opportunity.

Coaches

Finally, the coaching infrastructure remains poor and expensive. The number of courses available to those aspiring to become padel coaches is limited and too expensive. The minimum level of accreditation in the UK costs £650, and it only covers group lessons. Many of those attending the courses wouldn’t even have the skills of an intermediate player. Courses for more advanced levels and a genuine padel coach pathway haven’t even been developed yet.

With not enough good quality coaches in the UK, attracting the high calibre ones from Spain, Argentina and Italy is close to impossible. There’s no agreement between the LTA and the Home Office on the profession qualifying for International Sportsperson exemption, the cost of a visa application easily exceeds £5,000 per coach and it can take up to two years to actually secure the visa from the Home Office, and so our padel role models and guardians of talent are few and far between.

Solutions

Padel is an extremely accessible sport supported by a strong community approach and the demand is growing exponentially. If we do not think innovatively, we will miss out on people playing, keeping active and encouraging footfall into the capital.

It can also be expanded upon with food and beverage offerings creating further job opportunities, adding value to the local and wide economy. The sport enhances the fabric of London’s urban appeal and creates a dynamic and inspiring destination for all; it is a win-win situation.

There are numerous ways landowners, policy makers and sports club owners can be innovative and capitalise on this ever-growing sport:

The LTA should take an example from the Italian Federation, who upon seeing the demand of the sport, demonstrated foresight by enrolling all the tennis coaches for free in padel coaching courses, and either fully commit to backing the game, or let it have its own governing body who will.

To activate a space and improve urban attractiveness, pop-up short-term padel courts, such as the one in Tower Hill last summer, are ideal to introduce the sport and a new offering to the local and wider community as well as an incentive to encourage return to the workplace and to increase dwell time, and this should be embraced. Last summer’s Central London Alliance Padel Tennis Festival in the Crescent in the City of London, drove footfall into the City, also encouraging visits on weekends and bank holidays – with approximately 6,380 additional people visiting the Crescent over the summer – and contributed to a 900 per cent uplift in year-on-year sales for local businesses.

For longer term, sustainable solutions for unused land – from car parks (roof top padel club anyone?) to retail space, creating a padel club could be an ideal solution to breathe new life into the unused space, adding value to local residents, workers and visitors. Examples of creativity can be taken from market leaders, Stratford Padel Club, who transformed an old car park into one of London’s most popular community padel clubs.

James Forster, Director of Metric RE, commercial property experts exclusively advising business occupiers commented: “Institutional Landlords that are working on regeneration schemes across Greater London are in a unique position to capitalise on the growing popularity of padel. They have the scale of land available to truly curate a community. With so many new operators entering the market, picking the right partner who they can trust, on the right commercial model, is key.”

Existing sports clubs – cricket, hockey, rugby as well as tennis, should consider offering padel on un-booked courts, fields or even car parking spaces – adding an additional sport to the already existing offering and opening up their audience to a wider pool of individuals can only be of benefit. In turn, driving additional footfall to their current food and beverage offerings; increasing turnover with minimal additional costs.

Planners should embrace the opportunity on padel related applications and see the economic value as well as health and wellbeing benefits that padel can bring to their local and wider communities, and consider whether Metropolitan Open Land designated for sports activities could also embrace indoor structures with improved facilities further adding to the value of the site.

Chris Hayward, Policy Chairman of the City of London Corporation and previous Chairman of the City Corporation’s Planning & Transportation Committee stated: “Sport is transformative. From improving our mental and physical health to redeveloping landscapes, sport is the glue that binds people and communities together. Sport is crucial for the wellbeing of our residents, workers, and visitors. It can also help us reach new and diverse audiences and is a crucial tool for our soft power as a global city to boost domestic trade and global influence.”

To discuss any of the items in this article, speak to CLA at hello@centrallondonalliance.com